Valles Marineris: Facts About the Grand Canyon of Mars

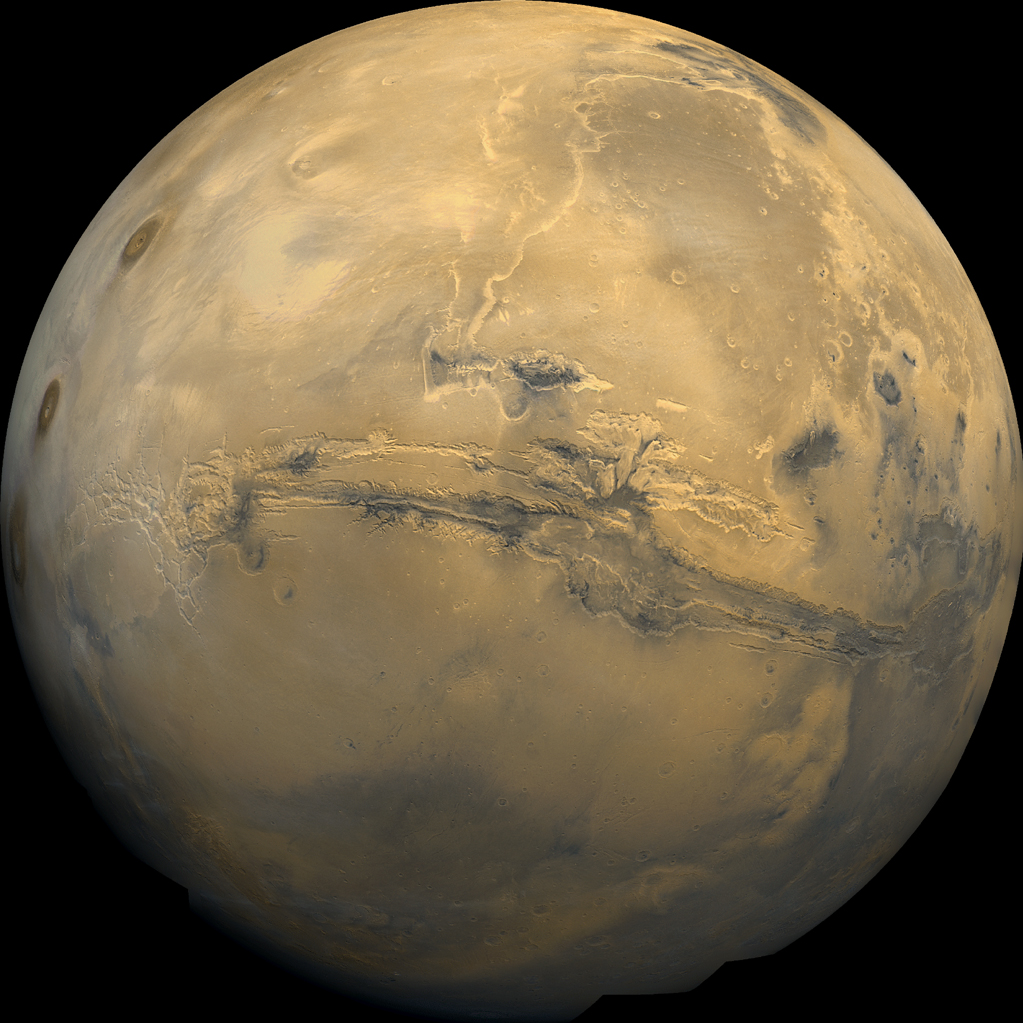

Covering nearly a fifth the circumference of Mars, the canyon system Valles Marineris reigns as the largest canyon system on the Red Planet. Dwarfing its Earthly counterpart, the Grand Canyon, the Martian feature is one of the larger canyons in the solar system.

Characteristics

Valles Marineris is a system of canyons that spans 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers). At some points, the canyon is 125 miles (200 km) wide. Regions can reach depths of 6 miles (10 km). If the system were located on Earth, it would stretch across the United States, from Los Angeles to the Atlantic coast.

By comparison, Earth's natural wonder, the Grand Canyon, is only 227 miles (446 km) long, 18 miles (30 km) wide, and 1 mile (1.6 km) deep. A windy channel on Venus, Baltis Valles, extends longer than the Martian system, as do a handful of rift valleys on Earth, which form along fault lines as the crust breaks apart.

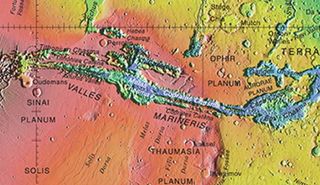

Valles Marineris stretches east-west just below the Martian equator. It starts in the west in the Noctis Labyrinthus, a system of maze-like valleys and canyons, and stretches around 20 percent of the planet to the chaotic terrain near the Chryse Planitia basin. (Chryse Planitia was visible to NASA's Viking 1 lander.)

The canyon system contains a number of different features that give clues to its formation. Collapse pits created by rushing water eating away at the land, massive floods, and seeping along canyon walls all point to water just at or beneath the surface at some point in the Martian history. Cracks in the crust, cliffs and walls, and landslides also exist along the expanse of Valles Marineris.

The vast canyon can be seen from Earth through a telescope as a dark scarring on the planet's surface. Features known as chasmata, steep depressions that resemble canyons on Earth, dominate the canyon.

The canyon begins in the Noctis Labyrinthus on the western edge, a region of material thought to have volcanic origins. Two parallel chasmata, Ius and Tithonium, stretch eastward, and contain lava flows and faults from the Tharsis Bulge.

Three more chasmata, Melas, Candor and Ophir, are connected on the east side of the parallel features. Their floors contain eroded material and volcanic ash. The floor of the Melas chasma contains the deepest point of the canyon system.

Coprates Chasma lies farther east, with well-defined layered deposits. These deposits may have formed from landslides or wind-blown material, although the region may once have housed isolated lakes.

This canyon, one of the lowest points in Valles Marineris, boasts a handful of its own volcanoes, though they are small compared to Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system, and its neighbors. The 400-meter high cones were only recently identified.

"We observed morphological details such as bulging of solidified lava caused by the injection of more-recent lava beneath the hardened crust, as well as characteristic surface patterns identical to lava fields on Earth," Petr Brož, from the Institute of Geophysics of the Czech Academy of Science, said in a statement. "This reinforces our assumption that we are looking at magmatic rock volcanism and not liquid mud."

"In geological terms, the volcanic cones are very young, just 200 [million] to 400 million years in age," co-author Gregory Michael, of the Freie Universität Berlin in Germany, said in a separate statement on the research. This is surprising, given that the bulk of Martian volcanism took place around 3.5 billion years ago.

Eos and Ganges are another set of chasmata that contain volcanic or windblown deposits that have slowly eroded over time.

The Valles Marineris system empties into the Chryse region, one of the lowest regions on Mars. Any water from the canyon system would have flown into the lowlands, and it may have once contained an ancient lake or ocean.

Valles Marineris formation

Over the years, scientists have proposed a number of theories about the formation of Valles Marineris. Erosion during a water-rich past and the withdrawal of subsurface magma were both early possibilities.

Today, most scientists think that the formation of the Tharsis region may have helped the canyon to form. The Tharsis region contains several large volcanoes that dwarf those found on Earth, including Olympus Mons.

As molten rock pushed through the volcanic region to form the monstrous volcanoes 3.5 billion years ago, the crust heaved upward. The strain cracked the crust, causing large faults and fractures across the planet's surface. Such fractures, growing over time, birthed the enormous canyon system.

The spreading cracks caused the ground to sink and opened an escape for subsurface water. The upward rushing liquid broke down the edges of the fractures, enlarging them and washing away more of the ground while flowing past.

Signs of flooding are especially apparent at the eastern end, in the mesas and hills known as chaotic terrain. Rushing water poured through channels into the lowlands, carving a series of channels. Scientists do not yet know whether the flooding took place over a short span of time, or whether one overwhelming flood was accompanied by several smaller flooding events.

At the same time, canyons were slowly widened over smaller scales as seeping groundwater carried rock and sediment away in smaller quantities. Landslides also helped to enlarge the features, sometimes traveling as far as 60 miles (100 km). Lava flows and ash falling from the nearby volcanoes may also have played a role in forming the intricate feature.

Glaciers probably helped with the carving. Signs of acid-rock interactions in Valles Marineris suggest that giant ice formations may have helped to carve at least some of the extensive network of channels. Deposits of the mineral jarosite suggest formation by ice rather than by puddles of water.

"Jarosite is usually considered an evaporative mineral: it forms from acidic water that is evaporating," lead author Selby Cull, of Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, told Space.com.

"Getting an evaporating pool of water halfway up a 3-mile-high cliff is tricky, and the more we looked into the geologic context surrounding the deposit, the less likely a liquid water origin seemed."

The large canyon system was discovered in 1972 by its namesake, NASA's Mariner 9 spacecraft, the first satellite to orbit another planet.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd at @NolaTRedd, Facebook, or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook orGoogle+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd